Here’s why the most gender equal country in the world still isn’t gender equal

Last Monday, Icelandic women left work at 2.38pm – 14.8% sooner than usual – to protest the fact that although Iceland is the most gender equal country in the world, it’s still not actually equal.

You’d think that Nordic economies, with their state-gifted baby boxes and gender quotas for company boards, would have ticked “Achieved Full Gender Equality” off their to-do lists a long time ago. But to Icelandic women, things aren’t as good as they could be just yet. Among other issues, women are still paid, on average, 14.8% less than men (what’s known as the gender ).

Women in Iceland come together to fight for equality, shouting OUT #kvennafrí #womensrights pic.twitter.com/vTPFwfSoVk

— Salka Sól Eyfeld (@salkadelasol) October 24, 2016

The ‘Global Gender Gap Index’ rates how gender equal countries are by looking at ‘economic participation and opportunity’, ‘educational attainment’, ‘health and survival’, and ‘political empowerment.’ Iceland has been top of the ranks for eight years in a row – but its overall score has dropped since last year. This is partly because the wage gap has barely budged. At this rate, closing it would take around five decades. “That’s a lifetime,” president of the Icelandic Confederation of Labor, Arnbjörnsson told the press during the strike last week. “It’s unacceptable.”

How has Iceland made it this far?

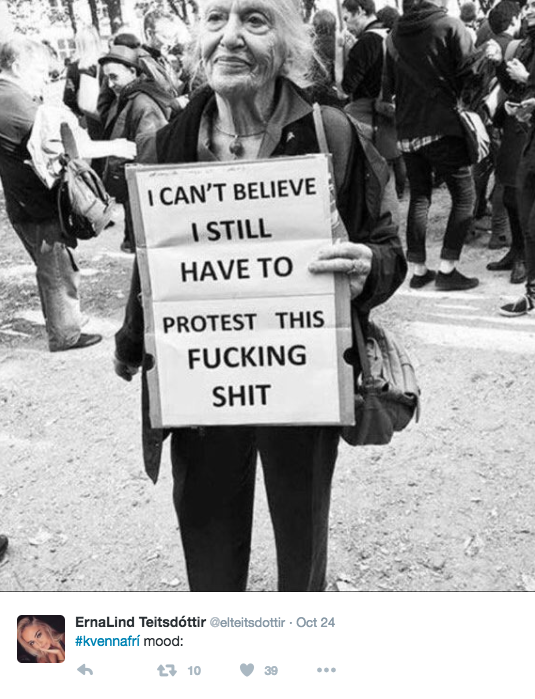

Icelandic women have been taking regular political action on a large scale for decades. In what’s become known as the great ‘Woman’s Day Off’, 90% of Iceland’s women (some 100,000 people – it’s a pretty tiny place) went on strike on 24 October 1975, not just from their workplaces, but from domestic work as well. Since then, Icelandic women have left work early on 24 October again and again – in 2005 at 2.08pm, in 2010 at 2.25pm – to demand a solution to pay inequality.

And although the pay gap persists, their action has paid off in other areas of life (as their consistently high gender equality ratings show). Rather than focusing on just on helping women ‘catch up’ to men, or excluding men from the process of discussion, policies on gender equality in Iceland often demand men’s active participation in bringing about change. As Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, Iceland’s prime minister from 2009 to 2013 and the world’s first open lesbian to serve as head of state, once told an interviewer, “[Men] have to realize that equal rights are not merely a ‘women’s issue’; they concern each and every family and the whole of society.”

In terms of domestic work, policies in Iceland try to create a more equal distribution of unpaid in the home. The Law in Respect of Children guarantees that children have a right to receive care from both parents. And unlike in other countries where fathers are reluctant to take up parental leave, recent estimates show that around 90 percent of Icelandic fathers use at least three month’s worth of parental leave.

And in the world of politics, Iceland has had a female head of state for 20 of the past 36 years. The country also broke ground last year by organizing an all-male "Barbershop" conference on gender equality, with a focus on violence against women.

... but it's still no gender-equal paradise

But the bit of the Gender Index that Iceland continuously underperforms on is ‘economic participation’. Equality of earned income and share of women senior officials and managers remains low.

The Sigurðardóttir administration tried measures like a 40% gender quota for corporate boards and a requirement to assess all public spending decisions in terms of their impact on equal rights. But three years after Sigurðardóttir has left office, the wage gap stubbornly persists, and flagship policies like the paternity leave program appear to have hit a wall after suffering several cuts to benefits.

Fixing these gaps isn’t just a matter of rights – it’s a matter of cost-effectiveness too. As Saadia Zahidi, one of the Gender Gap Report authors, emphasized to Quartz magazine, in an economy as small as Iceland’s, gender inequity exacts a cost in terms of human capital and competitiveness: “You don’t want to be wasting any of that talent, and you want to ensure that both women and men are able to combine their family or social obligations along with their ability to work.”

So when Icelanders say they need equality, they really mean it. Until then, we’re taking bets on what time they’ll leave the workplace next year – 2.42pm going once…?