We all know that money matters, but where did it come from and does it really make the world go round?

It’s been made from shells, plastic, copper, linen, and huge rocks. Nowadays it’s often just a number on a screen. It’s both a tool for exchange and an asset in its own right. It’s powerful if we all believe in it, and totally useless if we don’t. I’m talking about money.

Yes, when you think about it, money is one of the weirdest and most incredible inventions in human history. None of us can remember a world without money, so we don’t tend to question it that much. Except maybe to complain about how little we have!

Well, a new exhibition at the British Museum in London, called ‘Money Matters’ and supported by Citi wants us to stop and think about this thing that’s become so much a part of our lives, we’ve forgotten to ask where it came from. I went along to take a look and also have a chat to its curator, Mieka Harris.

“Money is a very complex issue for young people,” says Mieka. “Think about ‘cashback’ - adults buy things at the supermarket, they tap a card, and the cashier gives you money. What’s that about?!”

Now that it’s becoming more and more common not to handle cash at all and buy everything online or by card instead, Mieka is passionate about displaying art and artefacts which demonstrate the connection between the things we own and the money we bought them with.

One work, How I Paid for the Milk, by Central St. Martins student Olga Bagaeva, does just that by showing the code behind a digital transaction to make the point that swiping your card is costing you money too, just in a different form: all zeros and ones.

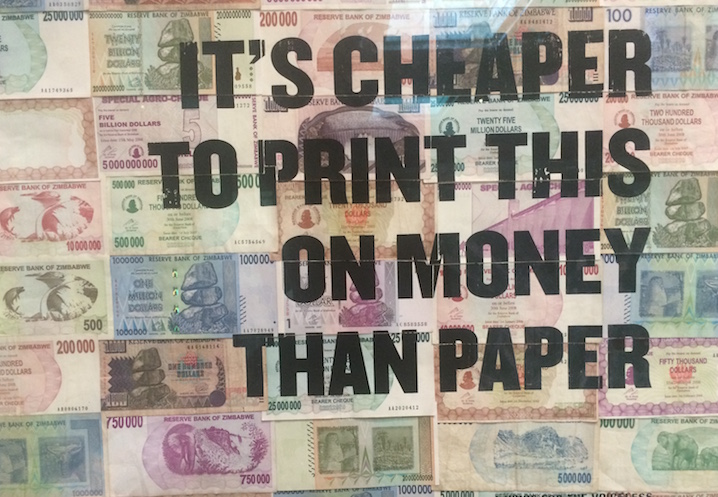

But there’s a lot of demystifying to do around what we might think of as more ‘normal’ forms of currency (notes and coins) too. I loved this really powerful collage of Zimbabwean bank notes in the Citi Money Gallery, a permanent exhibition at the museum. The notes are worth everything from 100,000 to 750,000,000,000, superimposed with the words “It’s cheaper to print on money than paper”.

I discovered that the museum runs workshops with schools in which the students get to handle these billion dollar notes, and are asked how they feel about them. Before they find out how little they’re worth, they tend to feel very rich, and even slightly scared about the level of responsibility that comes with holding the banknote. But once they’ve had explained to them and realise they’re basically holding the equivalent of a £2 coin, a common reaction is anger.

“Understanding how quickly the value of a banknote can change gets some emotional responses from the students,” says Mieka. “Many say they feel cheated, conned. They wouldn’t be bothered to go to work, if all they got in return was a worthless piece of paper, the value of which could change any minute.”

As well as teasing out the emotional relationship we have with money, the Citi Money Gallery also reminds us that money, politics, and power, are, as Mieka puts it, “intrinsically linked from the word go.” Economics is often presented as value-free, but a bit of digging into the history of money shows how far removed that is from the truth.

Take the Roman emperor Nero, the first ruler to appear on a coin, instead of a god. He ruled a huge empire and so putting his face on money was a smart way to make sure that people knew who was boss. However, because he was only a teenager when he first came to power, he was worried that his image wouldn’t be authoritative enough. His answer was to have the coins remade every couple of years to show himself getting older, fatter and hairier – a sure-fire way of demonstrating his power! Unfortunately, his plan backfired: a lot of people in the Roman Empire were extremely poor and hungry, and the sight of their emperor getting fatter by the year didn’t go down too well, making him increasingly unpopular among his citizens. Whoops.

And the examples don’t stop there. From coins minted by the suffragette movement in the 1920s saying ‘Votes for Women’, to a copy of The Wizard Of Oz with an explanation of the theory that the famous story is actually about a debate over whether to stick to the US gold standard, the City Money Gallery proves that money is a lot more than just a thing we use to get other things.

In fact, it stands for power, politics, culture, and a system that would fall to pieces if we all just decided to stop believing in it. Sounds a lot like the rest of economics to me!

Money Matters supported by Citi (Room 69a) and the Citi Money Gallery (Room 68) are on at the British Museum until 9 October 2016. Free entry.