Not investing into female engineers would be a big economic mistake

I am a mathematician, engineer, and Vice President of the Women’s Engineering Society. In my early working life, I remember being dragged out to be shown off as an example of that strange life form, the ‘woman engineer’ – when actually, I just wanted to get on with my work.

I thought I was just one of the first few of many to follow – but after a few years with no flood of women following me into engineering, and a few conversations along the lines of “Surely women just naturally aren’t as interested?”, for me to realize that we had to do more than just hope things would change.

So what would I say, if I were to try and convince one of those people who said women just ‘weren’t interested’, that they not only likely were – but also, that we need them to be? Why should we invest in getting more women into engineering, and keeping them there?

We need engineers.

In the words of senior engineer Sharon Ross, “There is no economy without engineering.” Any sector which sells or uses a product needs an engineer. Engineers create the buildings, software, machinery and equipment behind everything we buy and sell – from software in the banking industry, to the cars we drive, to machinery in a factory, to chocolate and makeup.

The engineering sector generates well over 25% of the UK’s total GDP. Engineers aren’t just in engineering – programmers, digital technologists, technical project managers and a range of other specialised engineers work across other sectors like retail or the creative industries. And they’re all in high demand.

“I have never worried about being out of work,” says Yasmin Ali, one of our members working as a control engineer at an energy company.

We need more engineers.

Engineering is facing a ‘skills gap’ – in other words, not enough people with the right skills exist to meet industry demand. Around two-thirds of engineering employers say a shortage of engineers in the UK is a threat to their business because they have had to put projects on hold or are expecting not to be able to deliver on future work. Around one third of companies across sectors currently have difficulties recruiting experienced STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) staff.

And that’s only taking into consideration the amount of engineers our economy needs right now. With the plans that government and businesses have for the UK in future, we’ll need to at least double the number of engineers graduating each year to build the train lines, roads, cities, products, and medicines we’ve got in store.

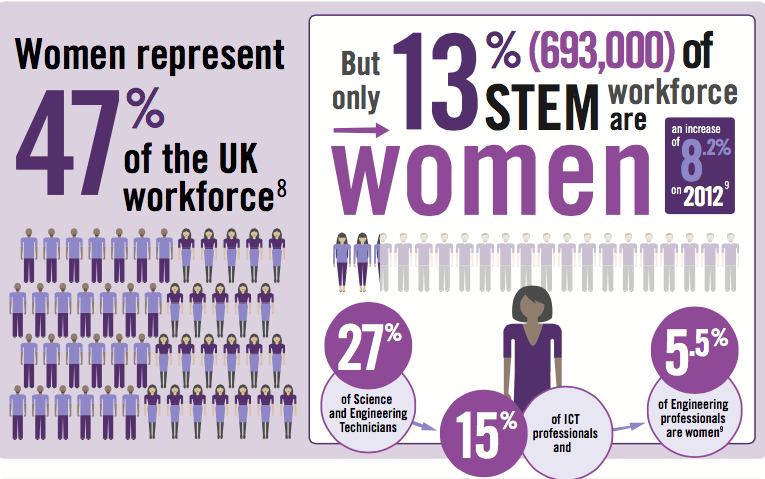

There are next to no women in engineering. It’s a problem for the skills gap – and it’s a problem for equality.

Only 9% of the engineering workforce, 6% of registered engineers and technicians (i.e. CEng, IEng, EngTech), around 4% of engineering & manufacturing apprentices and 1% of construction apprentices are women. The UK has the lowest percentage of female engineering professionals in Europe, while Latvia, Bulgaria and Cyprus lead with nearly 30%.

The proportion of young women studying engineering and physics has remained virtually static since 2012, and the number of women in engineering has stayed the same since around 2000 when the statistics started to be counted. Around 16% of engineering and technology undergraduates in the UK are female (Compare this to India, where over 30% of engineering students are women.)

Diversity matters: companies are 15% more likely to perform better if they are gender diverse. Diversity is crucial for innovation because a diverse and inclusive workforce is crucial to encouraging different perspectives and ideas.

And the lack of equality isn’t just costing women – it’s costing all of us. It is estimated that giving women the right to play out their full potential in all areas of work and industry could add as much as $28 trillion to annual GDP across the globe by 2025.

We’re doing our best to change things – not just because it’s good for the economy, but because women deserve it.

The good news is that in a survey of 300 female engineers, 84% were either happy or extremely happy with their career choice. Betty Bonnardel, one of her members who runs her own space and nuclear consultancy business, says: “I have always felt that engineering provided me with a career of opportunities and allowed me to achieve financially too.”

Engineering students are second only to medics in securing full-time jobs and earning good salaries. The opportunities to work in engineering and technical sectors are plentiful, well-paid and exciting, and women should get the same access to them as men.

The Women’s Engineering Society (WES) www.wes.org.uk started in the UK to support and campaign to enable women to stay in the technical and engineering jobs they carried out during the First World War.

Since then, we’ve challenged the laws, policies, and attitudes that stop women and girls from getting the same access to education and work as men. Our members do everything from social media campaigns (take a look at #LottieTour on Twitter!), to sharing stories of ‘Magnificent Women’ in engineering, to simply networking, linking, and mentoring each other.

Did you follow the #LottieTour with the amazing women in STEM @YMB1919 @WES1919 @Tomorrows_Eng #womeninengineeringhttps://t.co/MpNx8toZac pic.twitter.com/xntdwWoMl4

— Lottie (@Lottie_dolls) November 13, 2016

And more and more organizations are following suit. Coinciding with International Women’s Day, the International Network of Women Engineers and Society's regional body for Europe launches this week – a ‘network of networks’ highlighting how much work we’re doing across Europe and the globe to make sure women can take their rightful place in engineering and science.