The 'Panama Papers' came out last week...

For anyone who missed it, it was basically 11.5 million documents leaked from a law firm in Panama called Mossack Fonseca, which told us what we already know: really rich people sometimes keep their money abroad so they don’t have to pay their taxes at home.

What happened?

Well, Iceland’s Prime Minister has resigned, the UK’s Prime Minister David Cameron has published his tax returns, and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s PR team has been busy spinning this into a story about how he’s investing in the arts.

But they’re just a few individuals. And Mossack Fonseca is only the fourth biggest law firm that does this kind of thing. So, like the world's angriest reporter Jonathan Pie, we might ask ourselves what this really means on a wider scale: What exactly is the system that lets all of this happen, and are we okay with it?

But how exactly does the system work, and is that going to change anytime soon?

There’s basically three big players: the tax havens, the intermediaries (bankers, lawyers, accountants) and the clients themselves.

So, let’s take a look at the tax haven where most of the companies exposed in the Panama Papers were located: The British Virgin Islands.

Over half of the companies exposed in the documents are based in BVI. Why? Because the tax on business and investment income there is so low BVI has over 900,000 companies registered there, with only a population of 30,000. That's about 30 companies per person!

Low tax isn’t illegal, and keeping money abroad isn’t either. So what’s the problem?

Well, BVI does have a legal responsibility to know exactly who owns the companies incorporated there, otherwise there’s no way of knowing whether the money is really theirs. Turns out, often they didn’t know, and neither did Mossack Fonseca. And turns out, often it didn’t belong to the people it was registered under – a lot of them were fake names for people who didn’t even exist. Whoops!

Okay, so that’s where the money is stored. Who’s responsible for putting it there?

The intermediaries, or the offshore companies themselves – most of whom are in Hong Kong, the UK, and Switzerland.

You can tell just how completely legal this is by the fact that a quick Google of ‘Hong Kong offshore companies’ provides you with an 'Entrepreneurs Guide to Forming an Offshore Company in Hong Kong'. You can even buy yourself a ready-made Hong Kong company off the shelf - so called ‘shell companies’ where the license for the firm is created on paper but not used until someone comes along and buys it. It’s basically like buying wine: the longer it’s been around, the more expensive it is, except in this case it’s because it makes the impression that it’s somehow more legitimate because it’s been around for a while. So you set up a business, conduct it all via this Hong Kong firm, and then store your profits in a tax haven.

Who's involved?

ICIJ, the organization who uncovered all this, is releasing the full list of people and companies involved in early May. For now, we know that at least 12 heads of state are involved, and 14,000 others: this interactive lets you explore the power players among them, passport scans and all.

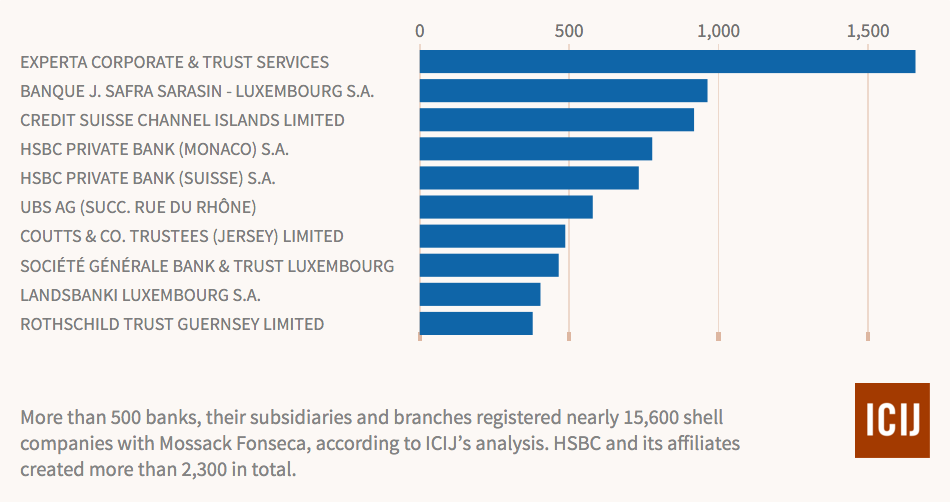

But they don’t do it themselves: thousands of bankers, accountants, and lawyers’ jobs genuinely depend on keeping this system flowing. Here’s the top ten banks involved: they’re definitely not the only ones.

So what happens now?

To Mossack Fonseca, the company whose documents were leaked...

Nothing. They insist they’ve done nothing wrong. You could argue they’re the ones who’ve been wronged: an investigation ordered by their lawyers is now ongoing in Panama as to how these documents were leaked in the first place. “Our industry is not particularly well understood by the public, and unfortunately this series of articles will only serve to deepen that confusion," the law firm said in a recent statement. "The facts are these: while we may have been the victim of a data breach, nothing in this illegally obtained cache of documents suggests we’ve done anything wrong or illegal...”

To the legal systems in the countries where it’s all happening...

We’re guessing, nothing much.

The problem is, there isn’t really an organization in place who could really do something about this. The European Commission passed legislation on Tuesday that companies with a turnover above €750 million need to publish their tax affairs, but that’s still just the EU.

The closest thing we’ve got is the OECD, who are having a meeting this week to convene a ‘panel of experts’ on the subject. They are essentially a club of relatively random, well-off countries describing themselves as ‘democracies and market economies’ who are pretty powerful and can probably make some decisions. Whether or not their decisions are genuinely representative and right is another question.

Seeing as a lot of tax havens also happen to be British Overseas Territories, the other person that could do something is UK PM David Cameron. He’d suggested a public register of companies in 2014, but the chair of the Cayman Islands stock exchange said that’d be a “terrible idea”, and nothing much happened after that. He’s also leading an anti-corruption summit in London in May for business and government to work together on how to clamp down on corruption and tax avoidance. Though it's worth remembering that Cameron was found to have shares in his father's offshore company. Mmmmm?

To the money...

Ah, the money. Well, whose money is it? Does it belong to the people who put it there? Or should it have gone to the tax authorities? In other words, is that money really ours? As an article in VICE put it last week, “If you live in one of the 200 countries and territories that Mossack Fonseca's clients call home – and, given the fact you're reading this article, you probably do – the story of the Panama Papers is your story. The money the law firm helps to hide should be used to pay for your schools, your highways, your hospitals.”

So what do you think? Are Mossack Fonseca right? Is this a violation of privacy? Is it a sign that we’re taxing people too highly that they’re even looking to put their money abroad? Is the current system fair? Is it moral? Or do we need to change things to make sure people pay their tax where it’s due?

We can’t really work out how to change our economies until we’ve answered those questions. Once we have, we’ll be a step closer to knowing what to do next.

Or we could just have a rave, like these protesters at an anti-Cameron rally in the UK last weekend.