The little town of Prato has been taken over by Chinese stuff. I had a look around

There’s a city in Tuscany, less than an hour by train from Florence, called Prato. Prato has been the one of the largest textile manufacturing bases in Europe for ages. If you’ve bought a shirt or blanket in Italy in the last century and a half, odds are the fabric came from Prato.

Since the Brexit vote and Trump’s election, everyone’s been talking about , and about all the places where the stuff we use everyday gets built, and all the places where it used to get built but doesn’t anymore. Where the stuff they used to make, made them. The ‘left behind’ places, where jobs and opportunities were easy to come by, but that supposedly aren’t doing so well now.

I wondered whether Prato was one of those places.

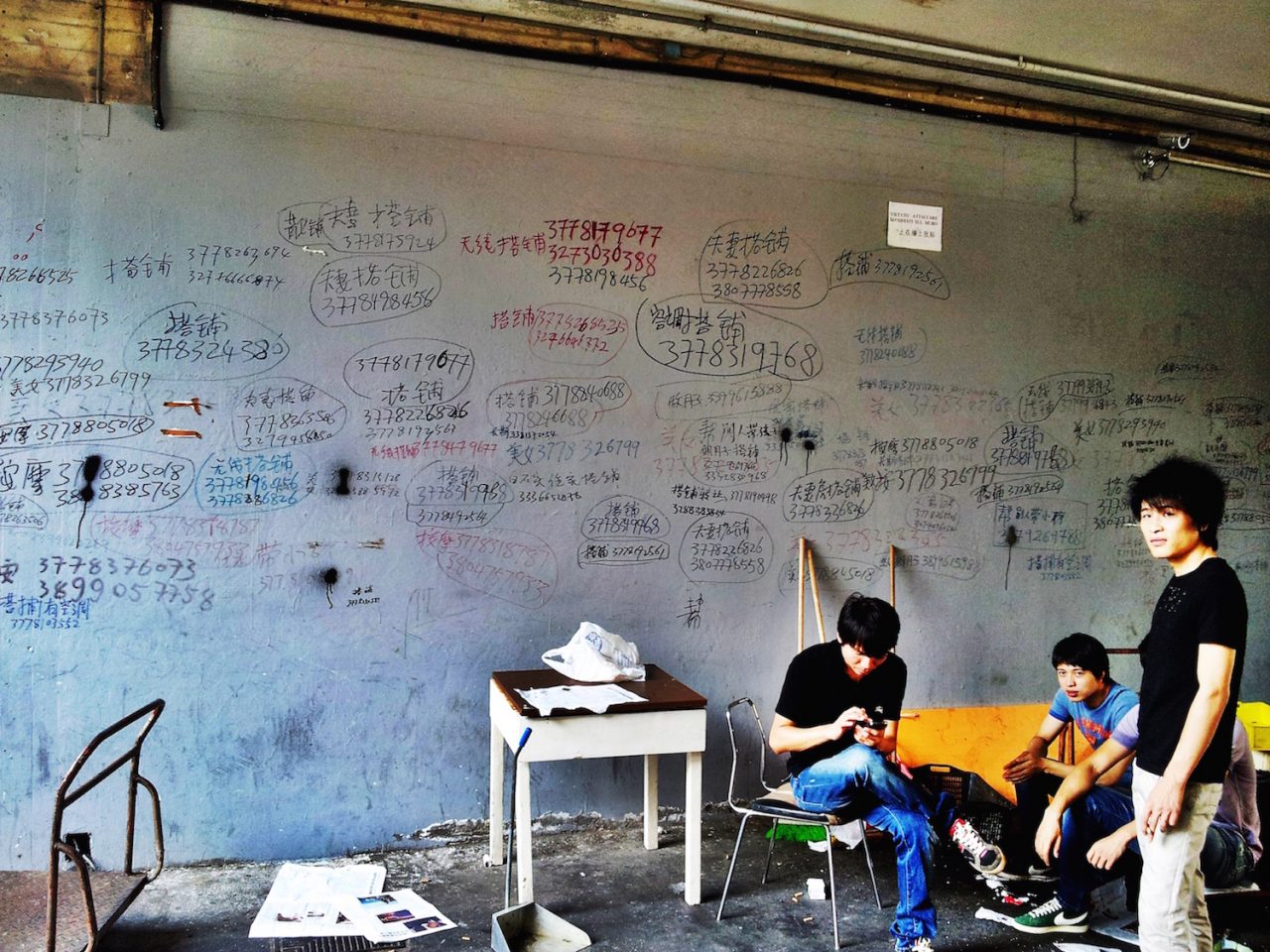

Prato is a small town – less than 200 thousand residents. It’s in the heart of Tuscany, but parts of it look like this:

This picture was taken next to Via Pistoiese, a road in Prato almost completely made up of Chinese shops: Chinese restaurants, Chinese wedding planners and photographers, Chinese fishmongers, Chinese supermarkets.

I spoke to Marco, a 38 year old construction worker, about the changes he’s seen here over the last 30 years.

‘Prato has evolved and grown in terms of population, but the majority… how can I say it… the majority it’s all Chinese. That ‘something’ that there was before isn’t there anymore, Prato’s traditions, the feasts… on the 15th of August we used to go to Feast of Santa Maria, we’d eat watermelons, you’d go there and see all the people from Prato… now what you see, it’s mostly managed by [the Chinese]….’

So when did Via Pistoiese swap cantuccinis for noodles and dumplings? Where do all these hand waving cats come from, and who buys them? Why do some areas of Prato, in short, look so Chinese?

The shift in Prato’s economy that brought us here began in the 1970s, when it moved from making textiles from recycled wool to producing finished products for the fashion industry – the stuff you actually buy in clothes shops. The biggest names in fashion came to Prato to get their stuff made.

But things went less well in the 1980s. As demand for the sorts of products Prato made declined, people began to lose their jobs.

Eventually the city began to adapt. The 90s were particularly good: the Lira (the Italian currency at the time) was cheap, i.e. worth less in terms of other countries’ currencies, so other countries could buy stuff from Prato and invest in Italian firms at a low cost. In 2001, the textile industry employed almost 50,000 people.

But an industry like this needs a lot of people to keep it going. Until the 60s, the extra workers Prato needed came from the countryside and around Tuscany. In the 70s and 80s, these jobs were taken up by migrants from the south of Italy, and in the 90s by workers from China.

Chinese immigrants quickly began buying and opening small firms, merging those firms, and replacing the older firms owned by Italian families. They focused on fast production of ready-to-wear fashion clothing and employed mostly other Chinese people, who were much cheaper than Italians. Failing Italian firms began cutting costs by closing down and renting their warehouses to Chinese companies instead.

“Prato never made ready-made stuff,” Emanuele, a 29 year old architect, told me. “It used to make the fabrics, not the finished products. This was the great strength of Prato. Those that destroyed us were the Chinese people in China, not the Chinese people here. But just as Prato was first in Europe with fabric-making, now Prato is the first in Europe for ready-made fashion, because of the Chinese community.”

‘‘It’s not true when people say ‘Chinese people steal our jobs,” said Alberto, a 30 year old chef. “Prato’s always been a city founded on this one sector, and from a certain point of view, fooled itself into thinking that the economic success it had for 10 years would last forever. Very few invested in other things.

Maybe if the Chinese hadn’t been here, many firms would have kept working, and been forced to innovate. Instead, they had the option to close their firm, sell it without paying taxes, and then rent their warehouses to the Chinese, thinking, ‘If there are some irregularities or the warehouse is not up to standard they won’t say anything,' and so on… so this is what happened.”

Today, Tuscany has the largest percentage of firms owned by Chinese citizens in Italy, and Prato has the largest share in Tuscany. More firms in Prato are owned by foreigners than Italian, and over 70% of those owned by a foreign national are owned by the Chinese.

I spoke to Du, a manager at a Chinese restaurant, to get his perspective.

‘I’ve been living in Prato for 12 years. As long as there’s jobs, everything is fine. If I work here, and earn, say, 800 euros ($830), I can spend 200 euros ($210) to live, that’s enough. In China, if I earn 3000 renminbi ($430), I need to spend 5000 ($720) to live. You can’t make it.’

Chinese people in Prato created demand for Chinese products, food and services. Shops and firms catering to these needs started to appear. ‘If you come to a neighborhood like this one, and you feel thrown into China, because everything is Chinese,” said Alberto. “This community slowly started to open their own shops, to import this stuff from China, to create all these little supermarkets where many Italians also go shopping for electronic stuff, or to get their mobiles fixed.”

Some say this has made the city a better, more interesting place. Cosimo, 29, said it’s been enriching, bringing things you never found before to the city, rather than the tacky feel of the influence of tourism in places like Florence.

Others, like Giulio, an 80 year old man who used to own a textile factory, are more conflicted. “The young people from Prato all left to go work in France, Germany… if you look around, you can’t see a young person, it’s only the Chinese.

It’s just like 50 years ago, when there were no jobs and Italians went abroad, to America… it’s like back then. The firms are all closing down, especially in Prato. The only ones that survived are the ones that buy already made stuff from China to sell. There’s no more manufacturing here.”

Marco seems to feel the only thing propping up Italian firms anymore is loyalty. “We only work because we have regular customers that have known us for many years… otherwise you wouldn’t work. You get a new customer, you give them an estimate, and there’s always someone who can do it for half the price.”

There seems to be a general distrust that something about the way Prato has changed isn’t fair – that the rules aren’t the same for Italians and Chinese. An estimate cited by the president of the Tuscan region recently said the Chinese community in Prato allegedly dodges about a billion euros of taxes every year.

“If they would follow the rules we do…” said Marco.

“...and pay the taxes that we do…” Giulio added.

“Yes, then they wouldn’t have 50 people working for them, getting away with paying them 10 euros a day.”

Prato’s story is not unique. Cities and regions around the world are feeling the impact of firms moving abroad in search of cheap labor and low production costs.

As Alberto said, the one thing we know for certain is that it’s a complicated issue. “If you come to the neighborhoods where people interact with Chinese people daily, there are many sides to the story. There isn’t one that says ‘they’re good’, or one that says ‘they’re bad’: there’s the one whose son goes to school together with them and they play together, the one who works with them.”

But in the end, Marco points out, “People from Prato used to drive big expensive cars and Chinese people used to drive the Ape [a cheap and small three-wheeled truck]. Now people from Prato drive the Ape, and Chinese people drive the big cars.”