Strikes, ‘humanitarian crisis’, and the busiest week ever. What’s going on, NHS?!

Between junior doctor strikes, Red Cross allegations of 'humanitarian crisis', and a record number of hospitals having to send patients elsewhere, the NHS has been making headlines for all the wrong reasons recently.

So what's going on? We look at three major areas of pressure facing the health service to try and get to grips with the scale of the problem.

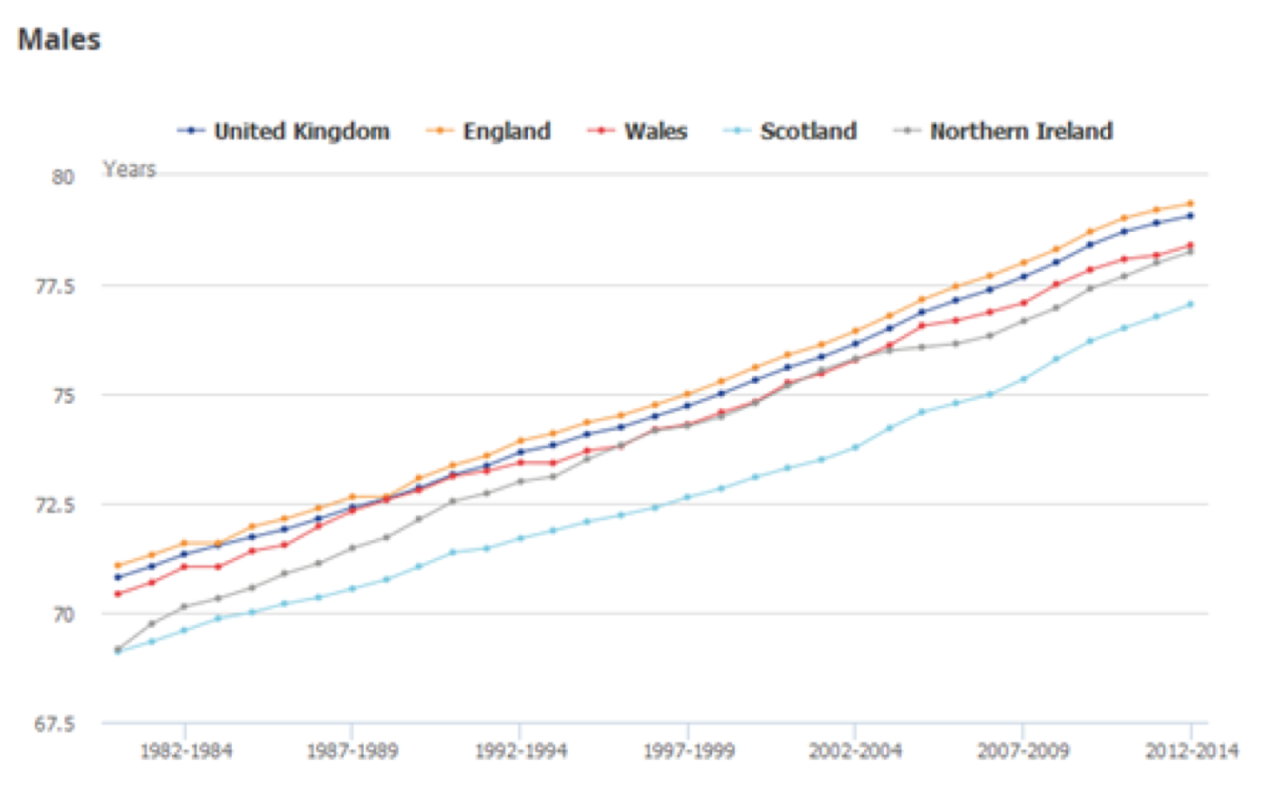

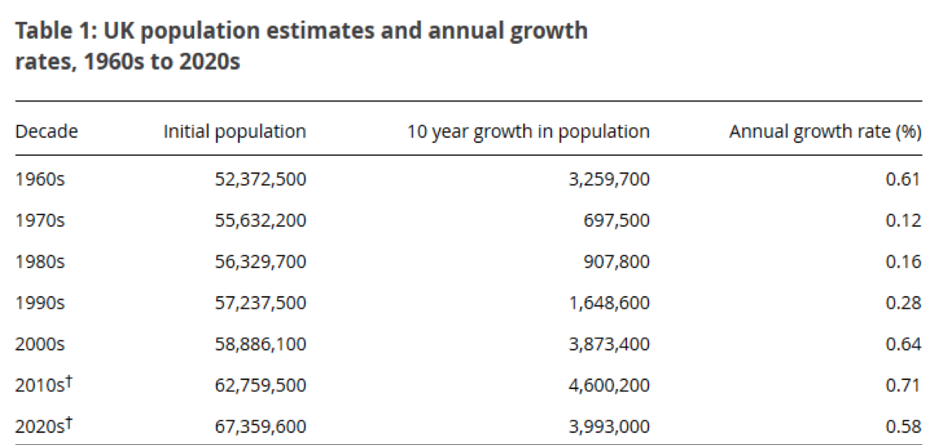

The UK has an ageing, growing population, which puts pressure on its health service

Basically, there are more of us, we’re living longer and we need to see the doctor more. From 1948, when the NHS was introduced, to 1960, the UK population grew by 2.4 million. From 1960 to 2015, it grew by 13 million.

That’s 65.14 million Brits, most of whom are living longer than they used to – the number of people over 90 years old per 100,000 residents has been on an upward trend since the 1980s. A lot of the delay in A&Es comes down to hospitals being unable to discharge elderly patients because of a lack of support available for them at home.

...and demand is increasing

And then there’s the current push for the NHS to be fully functional, 24 hours a day, seven days a week – the dispute that caused the recent junior doctor strikes.

According to NHS digital statistics, the number of patients attending A&E rose by 3.4 million between 2010-11 and 2014-15. The situation has got so bad that more than 20 hospitals had to declare a "black alert", which means they can no longer guarantee patient safety.

Not to mention the cuts to social services budget, originally intended to free up pressure on the NHS, but ultimately leading to a bit of a domino effect – lack of access to social services can push people into health services to fill in the gap.

To the junior doctors and their supporters, the proposal of a 24/7 workload without additional funding to match it will only cause more difficulty, putting patients' safety in danger.

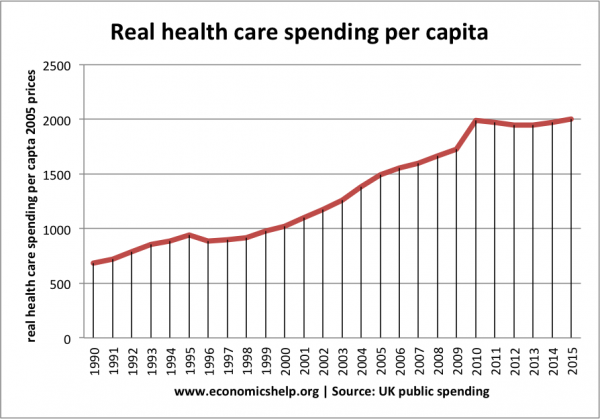

So where is the money, and how much of it is there?

You'd think it'd be fairly simple to find out how much the Conservative government has funded the NHS, and how much they've cut in comparison to the Labour government that came before them. Not so – the battle of stats comes down to a he-said-she-said of what you measure and how.

Unsurprisingly, Theresa May and health secretary Jeremy Hunt are pretty adamant that funding is going up. And in a sense, it is – from £97bn in 2010 to £120bn in 2017.

But the story doesn't end there. Firstly, Hunt told the House of Commons that this 1.6% boost to NHS funding was the sixth highest proportional increase in the NHS's history. But think tank The King's Fund took issue with this, bumping them down to 28th place.

Secondly, like you would with any budget, it's useful to think about this in comparative terms – i.e. how much is being spent on the NHS in comparison to the country's total wealth, and to spending under previous administrations. And in the NHS' case, that proportion is falling (as shown by the graph below.)

Considering the Conservative government's rhetoric that one of the prime purposes of the UK economy is to be able to “support the vital public services and institutions upon which we all rely – to invest in the things we hold dear,” it seems strange that when GDP – the main indicator the government uses for measuring how 'strong' the economy is – is going up, proportionate funding of the NHS wouldn't go up with it.

So what is this really about?

In response to the Red Cross' claim of humanitarian crisis, the doctor's union BMA insisted that "Theresa May cannot continue to bury her head in the sand as the situation in our NHS and social care sector deteriorates." With a third of hospitals said to be failing around the country, it's hard to argue with them.

To opponents of the Conservative government, the lack of funds going towards the institution in proportion to the wealth of UK as a whole is a question of values, not finances. And as the former chancellor Nigel Lawson said, the NHS is “the nearest thing the English have to a religion.” In other words, it's not the kind of thing you'd want to get on the wrong side of the public about.

That being said, the money needs to come from somewhere – and it's a lot. Independent government watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, says funding will need to rise by 2% a year, (an extra £88bn) by 2067 to support the institution – let alone secure the 24/7 service the government seems to want.