Content warning: This piece discusses illegal drugs and drug use.

“So, what do you do for a living?”

Most of us get asked this question a lot. Asking people how they get their money is the ultimate smalltalk fallback at parties, a way of weeding out weirdos on Tinder (Dolphin shaver? Alright, mate), and the favourite opening gambit of those annoying chatty people you’re always sat next to on planes.

But not all of us have the sort of jobs you want people knowing about. Take drug dealers. A 2007 study by the Home Officer reckons there’s 70,000 operating in Britain (that’s about the same number as food retailer the Co-op employs), although it’s difficult to be sure about that because the whole illegality thing makes drug dealers pretty reluctant to list their occupation anywhere.

But what’s it actually like to work as a drug dealer?

Talk to drug dealers about their work, and it pretty quickly becomes clear that drug dealing is in many ways like any other job. When asked what they like about their line of work, most mention earning potential, flexible working hours and the chance to be their own boss. Those are the same things employees in legal industries say they want most.

And just like other freelancers and entrepreneurs, many drug dealers talk enthusiastically about plans to expand their customer base, diversify their product offerings and/or seize on a profitable exit strategy, while griping about tenuous job security and having no work benefits like pensions, healthcare, and, um, not going to prison.

And is the money crazy good?

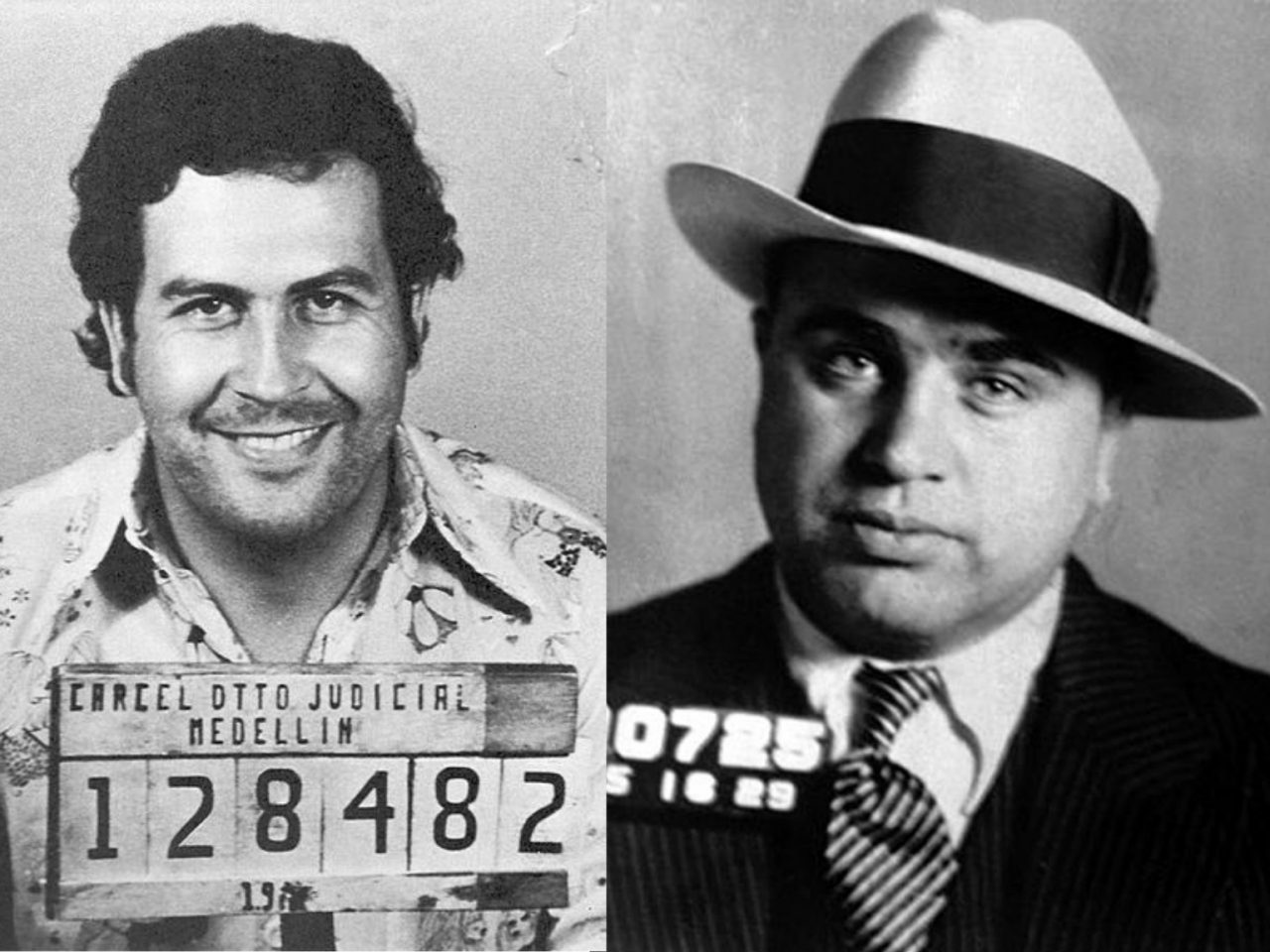

According to the University of Chicago, independent drug dealers (i.e. not the Pablo Escobars of this world) earn around $20,000-$30,000 (£15,000-£23,000) a year. That’s lower than the average full-time salary in both the US (about $41k/£31k) and the UK (around £29k).

But a direct comparison is misleading. For a start, drug dealers don’t pay any income tax or National Insurance on their earnings, which cost Brits earning that £29k average about £6,000 a year. Secondly, most dealers only do the drug thing part time (about three-quarters of them hold down another, legal full-time job). So they’re getting more money per hour of work.

Drug ‘salaries’ can also be attractively high if your other work options aren’t great. Not all drug dealers are low-skilled and/or lack educational qualification, but for those that are, drug dealing can offer much better returns than working in places like McDonalds, where the average Shift Manager brings home just £17,000 a year.

Can anyone become a drug dealer?

Our job here is to better understand the inner-workings of our economies, not suggest career choices, but in theory, yes. As careers go, drug dealing seems to have pretty low barriers to entry. You don’t need any sort of special training or qualification and you don’t have to lay out lots of money to get started (most drug dealers start off as drug users who sell on some of their own supply).

It often helps to have some initial connections to people already involved in the drug trade (to both source your product from and to mentor you on how to minimise the risks) but thanks to the internet, you can easily access both drugs and advice via things like the dark net or online forums.

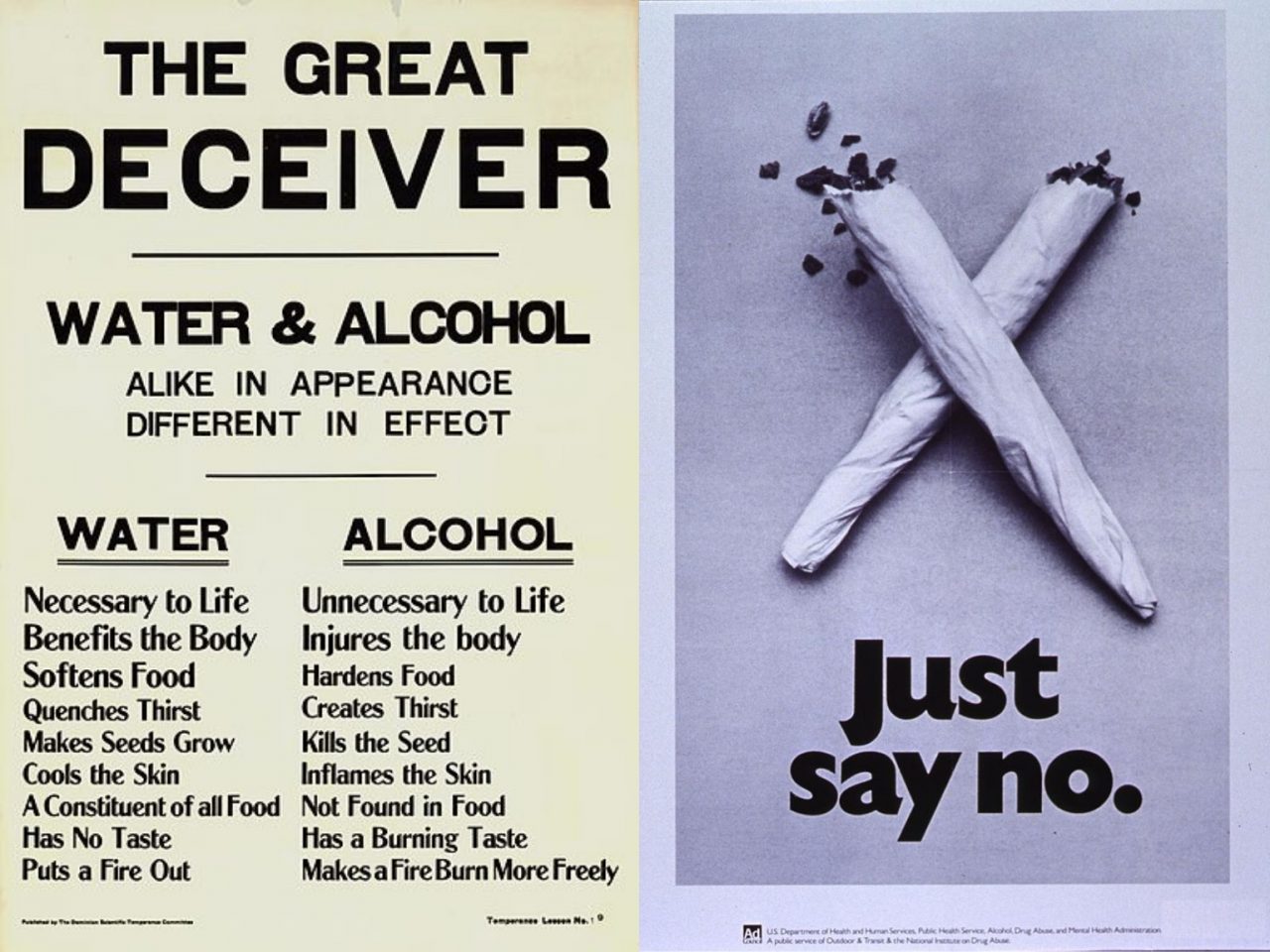

Of course, there are two big things that stop people considering a drug dealing career: moral objections to drugs and not wanting to break the law. Although related, these two concepts are not the same. Some people believe drugs are inherently bad - that they cause people to act in dangerous ways, that they spark other crimes like theft and murder, that they kill, or cause serious mental or physical health problems for many of them people who take them. (About 2,500 people die each use from legal and illegal drug misuse.) These people would presumably never wish to be involved in the drug industry, even if it was legal to do so.

But there are other people whose moral objections are solely related to the criminal aspect of drugs: such as the fact that they are a key money source for violent gangs or that they cause poor, vulnerable, often young people in both the drug-growing countries and in the UK to get mixed up in criminal enterprises.

And, of course, there are people who don’t have any moral objection to drug use or dealing but don’t want to risk getting involved in a business that could easily get them sent to prison (for life if the drugs are Class A like cocaine and MDMA). Legalise all drugs, and it’s a fair assumption that at least some of these people might be interested in getting involved in the industry.

How many people we talking here?

It’s difficult to say. If we use drug use as a proxy for how people feel about them, then there’s a pretty large number of Brits who don’t find illegal drugs immoral enough to refuse to consume them. A decent chunk - 9 percent - say they’ve taken them in the past year. For young adults (age 16-24), that figure rises to 20 percent. And these people are handing over a fair bit of their money for drugs: the Home Office reckons the drug trade is worth £5.3 billion a year, which is almost double what Brits spend on books, video games or films.

Another option is to look at a legal drug industry: alcohol. Most Brits (57 percent) drink socially, and the UK has 770,000 alcohol-related jobs, according to the Institute of Alcohol Studies. Some of those roles are highly-paid and super prestigious. Master Sommeliers, aka the world’s best wine tasters, can make over £100,000 a year.

Plenty of people will find the idea that the drug industry could ever function like the alcohol industry ridiculous. But the two aren’t as far apart as we may think. After all, there are places and times where alcohol has been considered an illegal drug (such as in Saudi Arabia now, or in America from 1920-1933).

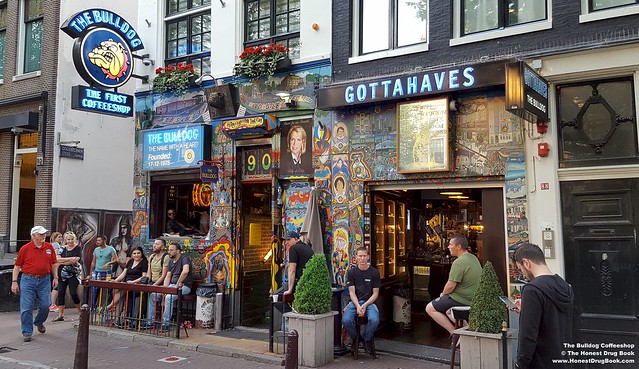

And there are places and times where drugs like cannabis and cocaine are or were legal. (Canada, Uruguay and several US states have recently legalised cannabis, and cocaine was perfectly legal in the UK before 1915). Looking at those times and places can give us an idea of what might happen to drug industry employment if all the drugs that are currently illegal in the UK were legalised.

Legalisation would probably create thousands of new jobs

It seems pretty logical to guess that making it legal to sell drugs would result in more people selling drugs. But there’s a much better reason to assume there would be a huge rise in drug-industry employment following legalision: it would lead to the creation of lots new auxiliary jobs. Think of pretty much any company you know and it’s clear that legal businesses don’t just hire people to sell their product. They hire people to market it, design its packaging, write website copy about it, file taxes related to it, talk about it at conferences… the list goes on and on.

In Canada and the ten US states that have recently legalised cannabis, a lot of people are excited about all these new jobs. One cannabis-information company released an e-book of the “500 hottest cannabis jobs”, which ranged from “cannabis tax specialist” to “food and edibles product development manager”. The newspaper Marijuana Business Daily claimed up to 230,000 new US jobs have already been created in the industry. A cannabis analytics firm says that number could double by 2021. (Of course, all these companies have an incentive to highlight the positives of the industry.)

This is good news if you - like almost every politician and economist - are a fan of job creation*. Employed people often need less welfare, pay more tax and spend more money, which leads to more businesses, making more profits, paying more tax, and so on.

(*Of course, you may think that we’d have happier people and a healthier planet if we weren’t so obsessed with having absolutely everybody in full time work all the time.)

But that doesn’t necessarily mean unemployment would go down

That’s because for those new drug industry jobs to dent the unemployment rate they have to bring new people into the workplace, as opposed to just encourage already-employed people to switch industries.

Some economists think different types of drugs - say alcohol and cannabis - are something called substitute goods, which means if people are buying more of one they’ll buy less of the other. Say lots of people stop hanging out at bars on Friday nights and start hanging out at Amsterdam-style coffee shops. Bars might lay off some of their staff. Coffee shops might then promptly hire them. (After all, there’s a heavy overlap in required skillsets). The number of people in employment, however, hasn’t changed.

Of course, other economists disagree entirely and say drugs are complementary goods - buying more of one makes people buy more of the others. In the example above, that would mean both coffee shops and bars would be hiring more people.

In the US states where both alcohol and cannabis are legal, it’s not yet super clear who is right. The Distilled Spirits council says legalising marijuana has had “no impact” on drinks sales. Forbes says it has caused a 15 percent reduction.

Legalisation won’t help most long-term unemployed, but it might help those with criminal records

Unemployment in the UK as of March 2019 is 3.9 percent, the lowest level recorded (the unemployment rate doesn’t include people who are not actively looking for a job, like students, homemakers and people who are too unwell to work).

When the unemployment rate is low, it tends to be easier for people to get a job and harder for employers to find enough staff. So the people who are still unemployed are probably particularly difficult to get into the workplace for some reason.

They could have a unique skillset that means they’re looking for the sort of highly specialised role that doesn’t come around often. They could be determined to hold out for the absolute perfect position. Or, they could lack the skills and behaviours that most employers consider essential. And for these people, there’s little reason to think new drug companies would want to take on difficult or low-skilled employees any more than other companies.

With one possible exception: those whose undesirability amongst employers stems from them having a drug conviction. Employers are extremely prejudiced against people with criminal records: half of them say they won’t hire ex-offenders. That makes life hard for the 42,000 people in England and Wales who are handed a criminal record for drugs each year.

But what if companies started selling the same drugs these people were convicted for using? It seems likely that these business owners would be much more chill about hiring people whose only offence was enjoying the product they're now selling themselves. They might even value their knowledge of the substance! Indeed, legalising drugs could make previous use seem less problematic to all companies, including non-drug ones.

Wages might well go up

Some jobs are considered better than others, and if the drug industry created positions which gave their new hires higher wage or better working conditions than they had before, almost everybody would consider that a good thing.

But would drug jobs be good jobs? There is some evidence they would be: Glassdoor says cannabis jobs in the US pay 11 percent more, on average, than the median US salary (the median is the salary of the person who has exactly the same number of people earning more and less than them).

And if the drug sector does indeed provide new jobs at good wages, it could even boost pay in other industries. When people have multiple job options, firms have to compete for their labour: and that usually means raising wages or offering other perks and incentives.

Employers battling it out to provide better jobs would be especially welcome to the thousands of Brits who currently work minimum wage and/or zero-hour contract jobs, who often struggle to get by.

But there is a darker alternative: employment plunges as more people use drugs

A major argument against legalising jobs is that it will create more drug users, more drug-related accidents and illnesses, and more addicts. It’s not hard to see how that could negatively affect employment rates: people could become too ill or drug-dependent to work (and potentially end up on welfare, pushing up the tax bill), or do something fireable while high* (either inside or outside of work). Plus there’s the argument than in and of itself, we don’t want to become more ill, irrespective of the effect on work.

These concerns shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand. Some studies suggest cannabis use has indeed gone up in places where it was legalised. And it is a fact that drug use has contributed to thousands of people dying an early death, becoming addicted and/or becoming seriously unwell. There is a link between cannabis use and psychosis, for example.

At the same time, it’s worth noting that the medical benefits of illegal drugs like cannabis and ketamine have also been widely touted, and that access to these substances could actually improve unwell people’s ability to work.

*after all, we’ve all been to an office Christmas party where a colleague has overdone it on the punch.

This may be a risk many people are willing to take

It seems sensible to consider concerns about drug misuse and work within the context of current alcohol use. Alcohol is indisputably harmful, both medically and socially. The Lancet, a highbrow medical journal, looked at how harmful legal and illegal drugs are to both individuals and society, and concluded that alcohol was much more harmful than any illegal substance.

Alcohol is also responsible for a lot of decreased productivity: it is behind around 17 million sick days (about 5 percent of the total). And alcohol is also to blame for at least some people getting fired or dropping out of the workplace. Indeed, six in ten employers say they’ve had problems because of staff drinking alcohol.

Crucially, though, none of these facts make Brits willing to give up alcohol. A petition to ban it (and tobacco) got just 197 signatures. When asked what defines Britishness, 69 percent of citizens say “pubs”. It’s not that people don’t know the risks of alcohol consumption. Instead, it seems many of them have decided that the risks are an acceptable trade off for access to something they consider fun, or relaxing, or a good way to socialise. Drug users presumably feel the same way. Society and lawmakers have to decide how much weight to give their preference compared to risks to their health and productivity.