Why do banks charge overdraft fees?

You don’t have to try hard to find someone who’s got some experience of bank charges. There are hundreds of thousands of people in the UK who are consistently (more than 10 out of 12 months in a year) going into an unarranged overdraft and being charged for it.

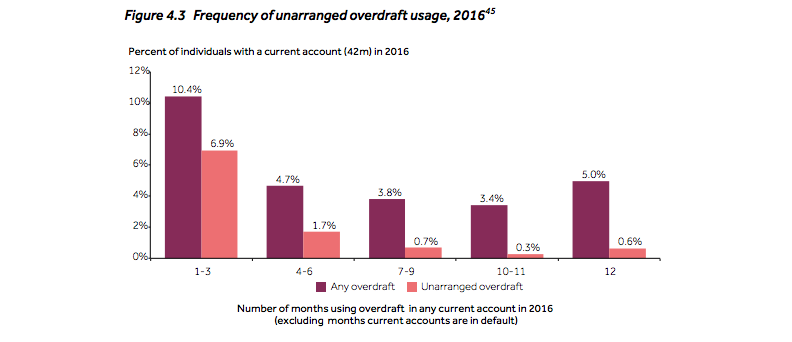

Most current accounts have an 'overdraft' system – you're allowed to spend a certain amount more than you actually have, and have to pay it back with a bit of interest. An unarranged overdraft is like an extra buffer to that buffer – if you spend more than your agreed overdraft, the bank will still sometimes let that payment go through, but you might be charged extra (most of the main UK banks charge between £5-10 a day.) Nearly 10 per cent of people using an unarranged overdraft used it for 10 months or more.

Let’s just stop and do the maths: 42 million people in the UK had bank accounts in 2016. 6.9 per cent of 42 million is 2.9 million (ish). That means there are hundreds of thousands of people in the UK who are consistently (more than 10 out of 12 months in a year) being allowed to spend more and borrow more from their bank than they can afford.

We asked Ahmad, a full time bus driver, what his experience was. He reckons he’s spent about £500 in total on unarranged overdraft charges. “I’m not exaggerating,” he says. “Sometimes you’ve got enough to get by, but sometimes if you get paid at the beginning of the month, that money won’t stay until the end of the month.”

The Financial Conduct Authority, which polices (technical term: regulates) banks behaviour, says it’s got a few main concerns about unarranged overdrafts. One is that the charges are confusing, and often take people by surprise. It's also concerned that the people who are using these overdrafts over and over again shouldn’t be being allowed to. They think repeated use shows that someone’s in an unhealthy debt spiral. And that they’re “being given access to a service that seems unsuitable for them, and which may be contributing to potential financial distress”.

So why are you allowed to spend more money than you have?

Some say banks just shouldn’t be allowed to let people spend more than they have. “If there’s no money, there’s no money,” said one woman we spoke to on the issue. "They give you money when they know you don’t have it, the debt’s piling up and you don’t know how to pay."

But there’s a reason the FCA hasn’t just straight up banned banks from doing it. For a lot of people having an unarranged overdraft (a buffer to your buffer) can be pretty useful. It means you’re not going to default on your gas bill because you haven’t been paid yet, for example.

The bankers themselves (or at least the trade body that represents them, UK Finance – which used to be called the British Bankers Association) defended unarranged overdrafts in a statement. They said (kind of vaguely) that people borrowing money is good for ‘economic growth’ and that it was never in a bank’s interest to lend money to someone who couldn’t afford to pay it back.

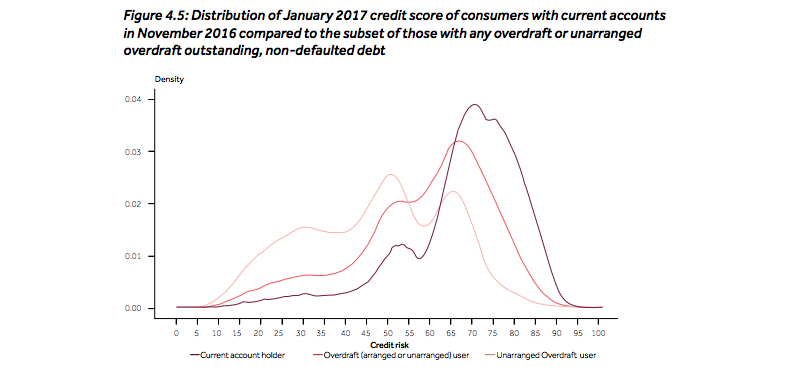

The problem is that banks currently don’t have to carry out credit checks (a process by which lenders work out if you’re likely to come good on a loan) to give you an overdraft. But the FCA’s research shows that the people who tend to use overdrafts are those who wouldn’t score that highly on a credit check.

People with overdrafts tend to have lower credit scores than people without, and people who regularly use unarranged overdrafts tend to have even lower credit scores than those who stick within their agreed limit. It might seem obvious – a credit score is a way of judging how ‘good’ with money someone is. A low credit score means the bank’s judged you to be less responsible with your money, so it follows that you might lose track, and spend more money than you have.

But there’s a chicken and egg thing going on here. It’s not just that people with low credit scores are more likely to use unarranged overdrafts. The FCA is saying that those stats prove that unarranged overdrafts and the charges that come with them are affecting ‘vulnerable’ people most.

And why do they charge you for it?

Overdraft charges are normally made up of a fee (often paid every day you spend in your unarranged overdraft) and a bit of interest on the loan. The fee is linked to the ‘risk’ the bank is undertaking by lending you that money – how likely it is to get it back, basically.

But for Willhelm (who we also stopped on the street to ask about it), it comes across as less of a way for banks to warn people off borrowing, and more a way of getting more money from people who are already vulnerable and down to their last pennies. “It’s greedy,” he said. “It’s how banks make their money.”

The FCA says it’s aware that charges make up part of the bank’s revenue on current accounts. In other words, it genuinely is part of how they make their money. The FCA’s concern is that a tiny proportion of people are making up the bulk of bank’s revenue from overdrafts.

It points to the example of one bank (which it doesn’t name). Only 5 per cent of its customers pay over £250 in overdraft fees per year, but those 5 per cent make up 50-60 per cent of the bank’s total revenue from overdrafts. In other words, a small amount of people (who happen to be likely to feel the negative effects most) are paying the bulk of bank’s revenues.

“Half of the people that used unarranged overdrafts were not even aware that they had done so ”

The FCA says it’s aware that charges make up part of the bank’s revenue on current accounts. In other words, it genuinely is part of how they make their money. The FCA’s concern is that a tiny proportion of people are making up the bulk of bank’s revenue from overdrafts.

It points to the example of one bank (which it doesn’t name). Only 5 per cent of its customers pay over £250 in overdraft fees per year, but those 5 per cent make up 50-60 per cent of the bank’s total revenue from overdrafts. In other words, a small amount of people (who happen to be likely to feel the negative effects most) are paying the bulk of bank’s revenues.

So could they be banned?

Predictably, banks aren’t too keen on getting rid of charges altogether. The FCA technically has the power to intervene, and says it could do if it thinks consumers are being harmed in a way that “needs to be addressed”.

It says there have been a lot of changes to encourage banks to be a bit clearer about what you’re being charged and when, but currently unarranged overdrafts are really complex – half of consumers don’t know they’re using an unarranged overdraft, how much they’re borrowing, or for how long.

The FCA asked for feedback from people across the financial sector, and is now looking in more detail at its options. UK finance said its members (the banks) are “committed to responsible lending”, and were constantly working on ways to make it all “clearer”.